Posted by: Claire Komacek

Although she is considered to be the greatest Pre-Raphaelite female artist, Marie Spartali Stillman is still virtually unknown and underrepresented in the canon of art history. One of a small number of professional women artists working during the second half of the nineteenth century, her work has largely been overlooked due to the fact that most of it resides in private collections, but moreover that her status as model to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood overshadowed her career as artist. Drawing upon her own Greek heritage and experience modeling for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Spartali painted images of active, empowered women that challenged the male gaze.

Spartali was born into an affluent Greek merchant family in London. Her father, Greek Consul-General to the United Kingdom and patron of the arts, frequently hosted garden parties to which he invited young, up-and-coming artists and writers; this is undoubtedly how Spartali’s exceptional, unique beauty came to the attention of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.1 They regarded her as a ‘stunner,’ ‘a woman so beautiful she ought to be painted,’2 and throughout her lifetime Spartali would come to ‘be most valued for her role as an artist’s model.’3

She was cited as ‘Mrs. Morris for beginners,’ after famed Pre-Raphaelite model Jane Burden Morris, and as a model for one of Rossetti’s paintings, her beauty left the collector ‘shocked with delight.’4 She, alongside her cousins Maria Zambaco and Aglaia Coronio, collectively came to be known as The Three Graces, as all three were noted beauties of Greek heritage, and of whom Spartali was deemed the most beautiful.5 Throughout her modeling career, she for numerous paintings by Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, as well as photographs for Julia Margaret Cameron.6

Discontent with being purely the recipient of male gazes, Spartali desired to become an artist herself, and in 1864 she begged her father to allow her to study drawing and painting under Ford Madox Brown, the eldest member of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. She trained with him for six years, during which she continued modeling for her artist-friends, and sat for Brown for several drawings.7

Spartali was trained in watercolors, a technique routinely taught to middle and upper class Victorian women alongside other ‘accomplishments’ such as music, singing, embroidery, and conversational French or Italian, together comprising an education that prepared young women for their roles as wife, mother, and hostess.8 Soft and delicate, watercolors were viewed as feminine in quality, and therefore insignificant; oil paint, on the other hand, was regarded as masculine, a messy, harder to handle media that needed to be mastered.9 Throughout her career, Spartali chose to work primarily in a mixture of watercolor, gouache, and graphite, innovating her own technique with the addition of heavy, opaque pigments and additives that gave her work a jewel-like tone and the overall quality of an oil painting. In her distinct choice of media, Spartali sought to break out of the conventional ‘gender confines of an upper-middle-class woman working as a professional artist during the Victorian period.’10

Spartali was highly devoted to her art and produced a prolific body of around 170 works.11 In 1867, after only three years as Brown’s student, Spartali made her artistic debut exhibiting her work at the Dudley Gallery in London where she contributed three paintings: an Ottoman pasha’s widow, the Theban poet Corinna, and the allegorical damsel Prays-Desire from Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene.12 Soon after, in 1870, she was exhibiting at the Royal Academy, which had only opened its doors to women students a mere ten years prior,13 and from which women were routinely rejected from exhibitions and denied professional memberships up until the twentieth century.14 Spartali displayed seven paintings there between 1870 and 1877;15 her routine acceptance to the Royal Academy’s exhibitions, which excluded even male watercolorists up until the 1880s,16 is a testimony to her talent and reputation as an artist. From 1867 to 1908, Spartali regularly exhibited paintings at multiple venues and had dealers selling her work on both sides of the Atlantic. She went on to contribute her work to the Grosvenor Gallery in London from 1877 to 1887, displaying a total of seventeen paintings, and regularly sent her paintings to Liverpool and Manchester galleries, as well as to various venues in the Eastern United States.17

In 1871, against her parent’s approval, Spartali married William James Stillman, an American painter, writer, and co-founder of the art critic journal The Crayon.18 Sixteen years her senior, Stillman was a widower with three young children, for whom Spartali provided a home and base to which William returned to from his travels as a journalist for The Times. Because of her husband’s erratic lifestyle, Spartali became the prime breadwinner for her family.19 From 1877 to 1888, Spartali and her husband traveled between England and Italy. There, Spartali became highly influenced by Italian Renaissance art and cultivated her mature artistic style. She went on to travel to the United States in the early 1900s where she exhibited her work at Curtis and Cameron’s Gallery in Boston, as well as Julius Ochme’s in New York, making her the only Britain-based Pre-Raphaelite artist to work in the United States.20 Throughout her career, she consistently exhibited several pictures a year and sold work regularly.

Spartali herself was extremely modest, indoctrinated in the Victorian mentality that women should neither ’make exhibitions of themselves’ nor compete with men professionally; thus, she never aggressively pursued an art career, but worked in a reserved, subtle manner, situating herself next to the male artists ‘without transgressing too many social barriers.’21 Despite her inarguable artistic success, Spartali never received the serious critical attention she deserved during her lifetime, largely due to the fact that it was deemed unsuitable for women to practice art professional, in conjunction with her choice of ‘feminine’ watercolor media and graceful artistic style. ‘Even by the time she had established a reputation as a remarkably accomplished painter, Spartali was praised in a newspaper column describing an 1889 event at the Royal Academy for her ‘beautiful and picture-like head.’22 Upon observing her work, art critic William Michael Rossetti remarked that ‘like most of her sex’ she is ‘not gifted with a strong eye for form,23 and even her obituary praised her ‘incomparable and faultless beauty’ over her artwork, claiming that ‘it can hardly be said that she had high creative power, and her mastery over the technique of art was never very complete.’24 Such comments not only speak to ‘the limitations that were imposed upon Victorian women, who were excluded from art academies and prohibited from studying the nude model, but also reveals the Victorians’ ‘cultural blindness to their tendency to relegate women artists to the status of objets d’art.’25

Spartali’s paintings adapt the typical Pre-Raphaelite themes of female figures and literary characters, in addition to traditionally ‘feminine’ subjects of landscapes and floral still lifes. Her paintings of women ‘revised the way Pre-Raphaelite women were represented.’26 As a model for many Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Spartali was depicted as a passive woman of idealized, sensual beauty, typically staring off into the distance, as seen in Rossetti’s A Vision of Fiammetta and The Bower Meadow, for which she posed.27 This reoccurring image of the gazing female, absorbed in self-contemplation, her eyes averted from the viewer, permits her sexual objectification, as she is non-confrontational to the penetrating gaze of the male viewer. Moreover, the Pre-Raphaelite woman’s gaze, read as her inability to attain self-knowledge, serves as ‘a metaphor for women’s political powerlessness in Victorian society.’28

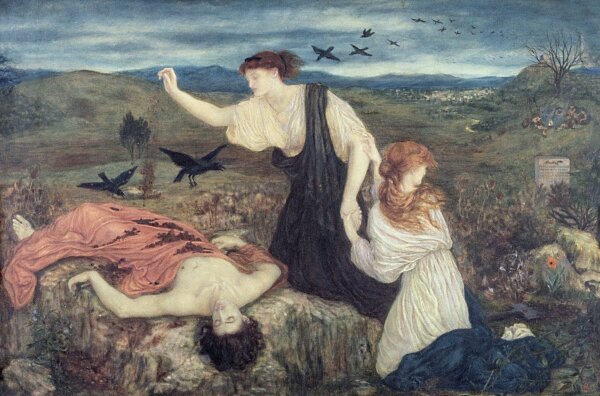

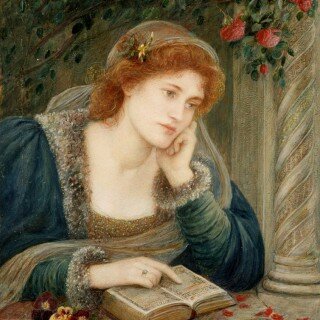

Spartali’s paintings ‘reveal consciously feminist and political themes’29 by her depiction women projecting their own sense of agency. Her subjects typically stare out of the canvas, challenging the gaze of the viewer, and the majority of them are shown as learned intellects, deep in thought, reading opened books or skillfully playing musical instruments. Spartali’s renditions of the ‘gazing female’ rejects the relegation of woman as objet d’art,30 as their sexuality is neither overt nor idealized. Several of Spartali’s paintings actually present as feminist re-workings of male Pre-Raphaelite artists’ works on the same subject, as seen in John Everett Millais’s Mariana and Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, A Vision of Fiammetta, and Madonna Pietra. In these paintings, Spartali ‘dulls down the potency of the feminine sexuality’31 depicted by her male counterparts, presenting her subjects as ‘creative, empowered agents.’32 In fact, while Spartali gained fame as the model for Rossetti’s A Vision of Fiammetta, she is rarely credited for having painted her own version of Fiammetta first. Both works depict Boccacio’s last sight of his inamorata, but while Rossetti shows Fiammetta as a vision of delight, Spartali depicts her playing a mandolin. Within a year or two after modeling for Rossetti, she painted a second version of Fiammetta, this time in a red dress and practicing the art of singing, and correspondences between the two artists tell of the mutual respect they held for each other.33

To compare, Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix is immobile, trance-like, her hands lying limp before her, suggesting a lack of power to move or enact her own will. Posed in an attitude of ecstasy that is simultaneously spiritual and sexual, her closed eyes and sensual, parted lips serve to satisfy the male gaze. Her ‘sudden spiritual transformation’34 suggests something that is happening to her of which she is a passive participant. A glowing red dove, like that of the Annunciation, descends to bring her a white poppy, uniting the symbols of death and chastity.35 In contrast, Spartali paints a vastly different Beatrice, one who is active within the composition instead of a mere focal point for the gaze.36 She sits in contemplative thought over an opened book, which appears to be a religious text, pointing to a passage and directing the viewer’s gaze away from her body. Spartali has thoughtfully chosen to conceal Beatrice’s body by the ledge that she stands behind, urging the viewer to focus on her intellect and spirituality over her sexuality, a theme further put forth by the bundle of pansies that rests beside her book, the flower of thoughts.37

While Spartali worked within an artistic movement that emphasized beauty for the sake of beauty, offering up the female as a figure to be visually admired, she used her own conventions to paint women as active figures rather than sexualized objects.38 Her success as an artist is remarkable, given the educational, professional, and social limitations imposed upon women during the Victorian era. The first retrospective of her work, Poetry in Beauty: The Pre-Raphaelite Art of Marie Spartali Stillman, is currently on display at the Delaware Art Museum, showcasing approximately 50 of her paintings.39 The exhibition serves to pay tribute to Spartali’s involvement in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, while simultaneously bringing overdue critical attention to this significant woman artist.

1. Rowland, Elzea, The Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft, Jr. and Related Pre-Raphaelite Collections (Charleston: Delaware Art Museum, 1978): 166.

2. Orlando, Emily J., ‘That I May Not Faint, or Die, or Swoon’: Reviving Pre-Raphaelite Women,’ Women’s Studies, September 2009, Vol. 38, Issue 6: 614.

3. Jiminez, Jill Berk and Joanna Banham, Dictionary of Artists’ Models (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2001): 513.

4. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636.

5. Jiminez, Dictionary of Artists’ Models: 513.

6. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636.

7. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636-637.

8. Orr, Clarissa Campbell, Women in the Victorian Art World (Manchester: Manchester University Press: 1995): 150.

9. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 634-635.

10. ‘Museum Presents the First Retrospective of Female Victorian Artist Marie Spartali Stillman,’ Delaware Art Museum, published July 8th, 2015, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://www.delart.org/press-room/museum-presents-first-retrospective-of-female-victorian-artist-marie-spartali-stillman/.

11. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 637.

12. Marsh, Jan, ‘Marie Spartali 1,’ Jan Marsh, published January 6th, 2015, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://janmarsh.blogspot.com/2015/01/marie-spartali-1.html.

13. Orr, Women in the Victorian Art World: 54.

14. Orr, Women in the Victorian Art World: 6.

15. ‘Marie Spartali Stillman (English, 1844-1927),’ The Golden Age of British Watercolors, 1790-1910, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://arthistory.wisc.edu/exhibitions/victorian-watercolors/spartali-stillman-pensierosa.html.

16. ‘History of Watercolor,’ The Golden Age of British Watercolors, 1790-1910, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://arthistory.wisc.edu/exhibitions/victorian-watercolors/history_of_watercolor.html.

17. ‘Marie Spartali Stillman,’ The Golden Age of British Watercolors.

18. Rowland, The Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft: 166.

19. Oberhausen, Judith, ‘Art Union: Marie Spartali Stillman and William James Stillman,’ British Art Journal, Spring/Summer 2006, Vol. 7, Issue 1: 88.

20. Rowland, The Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft: 167.

21. Dorfman, John, ‘Marie Spartali Stillman: Renaissance and Renascence,’ Art & Antiques, published October 2015, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://www.artandantiquesmag.com/2015/10/stillman-paintings/.

22. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636.

23. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 634.

24. ‘Maria Spartali Stillman,’ Art Renewal Center, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artist.php?artistid=543.

25. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636.

26. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 616.

27. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 639.

28. Prettejohn, Elizabeth, Rossetti and His Circle (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1997): 27.

29. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 637.

30. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 636.

31. Dickman, Meg, ‘Sexuality vs. Sensuality in the Aesthetic Movement: Marie Spartali Stillman’s La Pensierosa in the Context of Aesthetic Half-Length Figures,’ The Golden Age of British Watercolors, 1790-1910, accessed November 30th, 2015: 1.

32. Orlando, ‘That I May Not Faint’: 637.

33. Dorfman, ‘Marie Spartali Stillman.’

34. Barringer, Tim, Reading the Pre-Raphaelites (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999): 146.

35. Barringer, Reading the Pre-Raphaelites: 146.

36. Dickman, ‘Sexuality vs. Sensuality’: 9.

37. Cirlot, Juan Eduardo, A Dictionary of Symbols, Second Edition (New York: Philosophical Library, 1983): 249.

38. Dickman, ‘Sexuality vs. Sensuality’: 9.

39. ‘Museum Presents the First Retrospective,’ Delaware Art Museum.

Images:

1. Beatrice – ‘Lire et Relire (Chronique n° 25), Vita Nova par Dante Alighieri,’ La Plume de l’Oiseau-Lyre, published March 1st, 2014, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://laplumedeloiseaulyre.com/?p=1669.

2. Girl Playing Music – Liston, Susan, ‘Girl Playing Music. Marie Spartali Stillman,’ Pictify, published October 28th, 2015, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://pictify.saatchigallery.com/241945/girl-playing-music-marie-spartali-stillman-british-pre-raphaelite-1844.

3. Fiammetta Singing – ‘Marie Spartali Stillman,’ Galeria Pintores Extranjeros, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://www.foroxerbar.com/viewtopic.php?t=10513.

4. A Florentine Lily and Antigone – ‘Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927),’ Nevsepic, published March 15th, 2013, accessed November 30th, 2015, http://nevsepic.com.ua/art-i-risovanaya-grafika/9834-marie-spartali-stillman-1844-1927-40-rabot.html.

MooreWomenArtists welcomes comments and a lively discussion, but comments are moderated after being posted. For more details please read our comment policy