How long does it take to get a sculpture of a black woman in a Chicago park? Two Lifetimes

Posted by: Elaine Luther

Why are there no sculptures of women in Chicago? In a city built by women, in a city that produced no less than Jane Addams and Florence Perkins, why is there not a single image of a woman in a public park anywhere in this great and expansive city?

Yes, there is that sculpture of Dorothy, from the Wizard of Oz, in Oz Park. But she’s a character, and a child.

Yes, there is the “fountain girl” near the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Lincoln Park — though had you drunk the water back when it was a drinking fountain, you’d have gotten Typhoid.

And yes, there are countless allegories across the city, Lady Justice, Lady Liberty, the allegory of labor and even the water. But no real, flesh and blood women, who lived and have stories to tell and who contributed to this city and inspired those who came after her.

That changes on June 7, 2018.

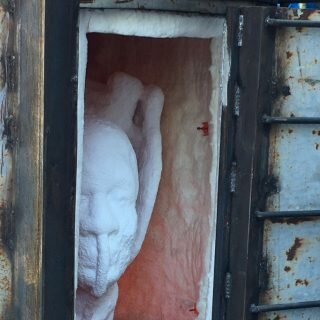

A bust of the poet Gwendolyn Brooks, one hand to the side of her face, in thought, her wise face in an expression of wonderment, has been cast in bronze and will be installed in Brooks Park in the Bronzeville neighborhood, on Chicago’s south side.

An additional casting of the sculpture will be poured in a resin that has a bronze look to it, and will be on display at the Oak Park Art League in May 2018, as part of a show on fair housing. Oak Park, a Chicago suburb, has worked hard to remain an integrated town and this show, “Art for Social Change: Sanctuary” highlights that history.

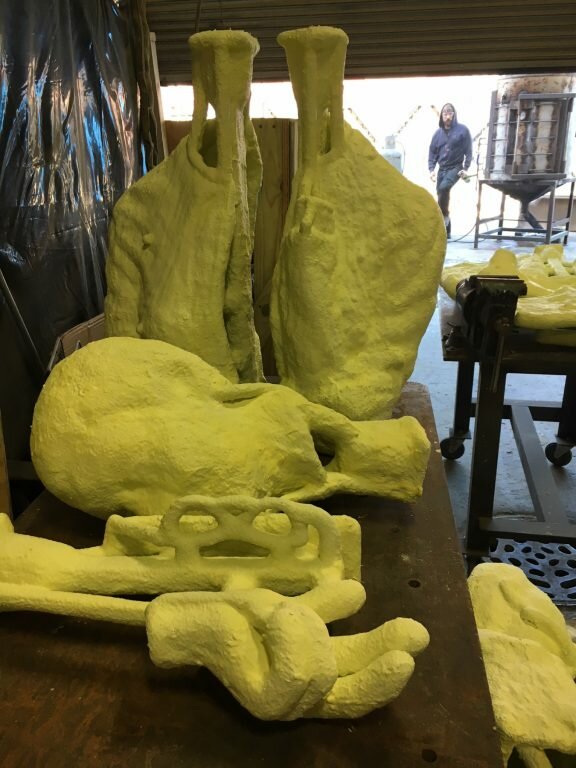

Sculptor Margot McMahon, who has sculpted many portraits in the 37 years of her practice as an artist, spent nearly a year immersed in the life and writings of Gwendolyn Brooks, reading her poetry, meeting in person with Brooks’ daughter, Nora Brooks Blakely.

Only after this immersive getting to know Brooks, through her family and writings, did she begin to draw and paint and then sculpt. This is the hidden part of the artistic process, the thinking, the mulling over. But the results are visible.

“What I did with the sculpting was to have these areas that are really expressive. And then other areas are very fine tuned and I used different tools,” McMahon explains. Brooks’ sleeves in the sculpture show energy and movement, while the shirt collar is more still. The gestures in the sleeves show Brooks’ energy. “But then you get to the collar and it’s very crisp and clean and in detail,” like Brooks as an editor.

Every texture in the piece has a meaning, even seemingly small details are there for a reason, and add up to a visual story of Brooks, so that the piece is more than a physical representation.

Whenever McMahon sculpts someone she searches for that spark, that gleam of their personality and then translates it into sculpture. She says, “I’ve gotta get that gleam and find it in the clay.”

She began sculpting in July of 2017 and around that time she met film maker Rana Segal, who documented the the process from sculpting to the molten metal pour.

While on the surface, it may seem odd for a white woman from Oak Park to sculpt the African American poet; Gwendolyn Brooks and the artist’s father (also an artist) were friends, and Brooks wrote an acknowledgment to her father, Franklin McMahon in her final book. This is a fact McMahon only discovered in the past year, and it was a delightful surprise to her.

“I knew they were friends, my mother talked about her and what they were doing together,” but she didn’t know about the acknowledgement in the book until she had already been working on the sculpture project for a year.

As a child, McMahon participated in an unusual exchange student program, where she spend two weeks living in Bronzeville with a young girl named Vanessa and her family, and then Vanessa came to stay with them for two weeks in Oak Park. In each case, the kids took each other around and showed the other how they spent their time.

The not-for-profit organization behind the idea of this sculpture is the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, into which Gwendolyn Brooks was inducted in 2010 and in 2017, the year in which Brooks would have been 100, they celebrated the Year of “Our Miss Brooks 100.” Their mission was to make sure that everyone in Chicago knows about Gwendolyn Brooks, who was the first African American person to win a Pulitzer Prize, and was poet laureate of Illinois from 1968 until her death.

The installation will include not only the sculpture of Gwendolyn Brooks, but also a re-creation of her childhood back porch, that her mother gave to her as her own space for writing. The idea is that young people in the neighborhood can come to Brooks Park, go there and write. And then they can publish their writing right away, but posting on a sharing wall that’s part of the installation.

A stone path, with each stone engraved with an excerpt from Brooks’ writing, will lead visitors from the porch over to the sculpture.

Support garnered for the costs of the sculpture’s creation to date includes a grant from the Poetry Foundation, support from the Chicago Park District, in the form of permission for the installation for a period of five years, as well as support for the day of the event, as part of their series, Night out in the Parks and printed posters and materials.

The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame continues to fundraise with an Indiegogo campaign, but one way or another, the sculpture will go in this June and Chicago will have it’s very first public sculpture of real woman, who lived and breathed and wrote, made an impact and inspired so many writers who came after her.

All photos courtesy of the artist. All artwork depicted is Copyright Margot McMahon.