Horseblinders (part one) by Harmony Hammond

Posted by: Joan Braderman

The following is from “HERESIES: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics,” Volume 3, No. 1, Issue 9, 1980. It is featured here courtesy of Joan Braderman, a founding member of HERESIES. ©1980 Harmony Hammond

In 1980, there is still pressure to answer the question, “What exactly is feminist art?” This does not reflect an interest in the function and concerns of art by feminists, or in what issues feminist art might address, but rather an obsessive need for a rigid definition of what a “politically correct” feminist art should look like. Curators, dealers, critics and artists-male and female-who come from the male-centered art world, as well as, unfortunately, many feminist artists and/or political activists – all have an investment in such a stylistic definition of feminist art. No matter where this fixation comes from, I find it equally disturbing in its narrow and dogmatic attitudes, its focus on the objectness of art, its distraction from the creative process and its avoidance of true critical discussion.

The main problem is that both the art establishment and the feminist community approach feminism as an aesthetic or a style. But feminism is not an aesthetic. It is the political analysis of the experience of being woman in patriarchal culture. This analysis becomes a state of mind, a way of being and thinking when it is reflected in one’s life. It can be articulated in art, and the art itself can in turn contribute to the process of analysis and consciousness. If art and life are connected, and if one is a feminist, then one must be a feminist artist-that is, one must make art that reflects a political consciousness of what it means to be a woman in patriarchal culture. The visual form this consciousness takes varies from artist to artist.

Thus art and feminism are not totally separate, nor are they the same thing. If this is not understood, if we view feminist art as an aesthetic represented by one correct style, then anything unexpected or unfamiliar is excluded. Art not derived from the white middle class is excluded. Radical new forms are excluded. The history of the patriarchal art world is and always has been the history of definitions and boundaries-the history of who has been excluded. To continue defining art according to this tradition affects the creative freedom and possibilities of those feminists making art and affects the possible roles of the art itself. Isn’t this part of what we hope to change?

The male-dominated art establishment has a need to qualify feminist art as just another style. I heard one well-meaning male critic, Carter Ratcliff, refer to it as “the avant-garde of the modernist tradition.” 1 While I believe he was referring to the power and innovative energy of feminist art, he reduced it to the latest development in a linear progression of inner art dialogue, where styles are bought, copied and subverted, resold and dismissed as “past art movements.” This attitude also implies that those women who are “good artists” will outgrow their feminist phase.

In 1976, Lawrence Alloway made a similar statement in his patronizing progress report on feminist art, where he informed us how we were doing, where our critical problems lay (in having no comprehensive theory of feminist art and no manifesto to state this theory), and what we now had to work for.2 At the same time that he criticized feminist artists for the discrepancy between their work and his theory, he attacked those very women who were out there actively creating work and developing theory. Since in his eyes no one woman’s ideas were comprehensive enough to stand for the whole movement, he discredited them all. In fact he saw the richness of diverse philosophies and aesthetics as divisionary rather than as the basis of feminism itself. In the end, Alloway’s report was an attempt to foster competition among women artists (as they strove for his critical approval).

The newest updated version of this patronizing intellectualization of women’s experience reflected in art is by Donald Kuspit, who, like Alloway, claims to speak for feminists since he apparently doesn’t think that we are yet capable of speaking for ourselves.3 He states that the “aggressive,” “revolutionary” feminist “critical intention” (the critical relationship to the existing order? to the masculine?) has nearly been lost because of “authoritarian,” “cosmetic,” “transcendental” feminism, epitomized at its worst by those women artists dealing with pattern and decoration in their work. This “authoritarian feminist art” arises from a “willful exercise of power-an attempt to achieve dominance, or at least prominence in the art world.” Kuspit makes no mention of the many hundreds of male and female artists all across the United States who are also working with these issues, nor does he mention the role the art market has played in the visibility of these works. I agree that no one style should dictate what other feminist artists should do. That is what I am writing about. But that is hardly what feminist pattern painters are attempting. Kuspit superimposes his own authoritarian position onto feminist art and then turns around and tells us that “authoritarian feminism in fact signals a split in the feminist camp.”

I say he is trying to split and divert us. Just what is the “old,” “revolutionary” feminist critical intention? Transcendental feminism? Authoritarian feminism? I have been a part of the feminist art movement since its beginnings, and have been around the national and international feminist communities quite a bit more than Mr. Kuspit, and I have never heard either of such a split or of these feminist categories. They do not exist merely because he says so. He assumes they do because he cannot imagine a feminist art that is not authoritarian, or part of a linear progression. Women do not think about feminist art this way. Such short-sighted thinking and language do not encompass the most unique and powerful aspects of feminist art. While obviously influenced by modernism, feminist art in its very diversity of content, style, form, media and technique proves that it is outside of and separate from that linear tradition.

However, the patriarchy has directly and indirectly affected feminist artists by defining, institutionalizing and marketing feminism. The pressure to weave a definable feminist art can only be exerted with capitalist threads attached. There is recognition and money to be made by men and women off of the commodity status of a standardized feminist art object. While women don’t seem to need or want such a thing, many are invested in spreading or popularizing a look that approaches their own. Unfortunately this too encourages distractions and competition: who did what first, who is a feminist artist and who isn’t (who is and who isn’t “politically correct”), and a subtle but important shift of focus from the work to the person. In some instances, the artist herself is marketed or markets herself within the male art world or the feminist community. This feminist art community, which is a loose network of many communities, galleries, organizations, support groups and individuals across the country, competes within itself as a marketplace for feminist art, artists, art schools and art magazines

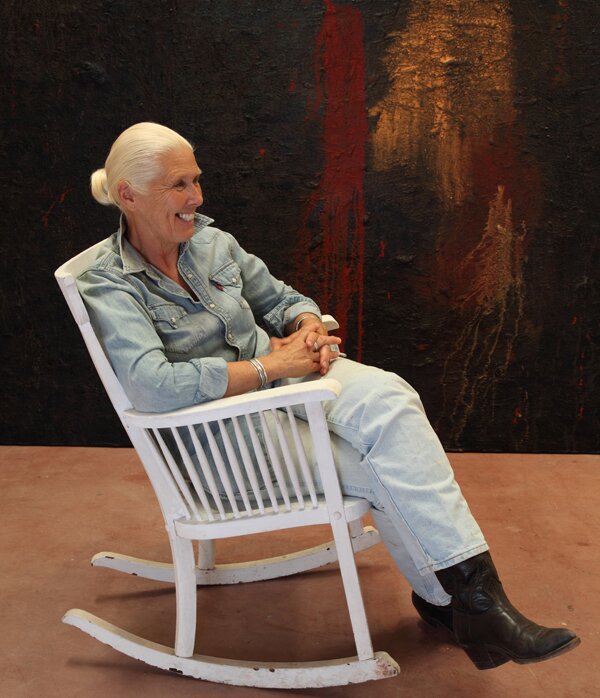

Harmony Hammond is an artist, art writer and independent curator who lives and works in Galisteo, New Mexico. Considered a pioneer of the feminist art movement, she lectures, writes and publishes extensively on painting, feminist art, lesbian art, and the cultural representation of “difference.” She was a founding member of A.I.R. Gallery and is an associate member of the Heresies Collective.

Photo of Harmony Hammond in her studio in 2010 courtesy of Times Quotidian

1 Carter Ratcliff at "The Personal and the Public in Women's Art," panel discussion at the Brooklyn Museum, 1977. 2 Lawrence Alloway, "Women's Art in the 70's," Art in America, May-June 1976. 3 Donald B. Kuspit, "Betraying the Feminist Intention: The Case Against Feminist Decorative Art," Arts Magazine, November 1979.