Posted by: National Museum of Women in the Arts

The following article is from the Summer 2006 issue of Women in the Arts

What distinguishes Australian Aboriginal art from other contemporary artwork is its basis in ancient tradition and the artists’ relationship to the land. Australian Aboriginal people maintain the longest continuous culture in the world, estimated to be more than fifty thousand years old. Aboriginal art is inherently linked to the spiritual realm and is rooted in ancient stories called ‘Dreamings.’ Simply interpreted, the Dreaming is the period during which the land and all life upon it were created by spiritual ancestors. These ancestors gave birth to humans, established the moral code known as the Law, and traveled the land to shape its natural features. The Dreaming overlays the landscape with mythical significance and creates a strong bond between Aboriginal people and their homeland. For thousands of years, Dreamings were communicated through painting, dance, storytelling, and other artistic expressions that served to connect the Aboriginal people to the creation era. These expressions were ephemeral and intended for initiated participants within the community. According to Aboriginal Law, participants were allowed to represent only Dreamings they have inherited through birthright.

In 1971, at the community of Papunya in the Northern Territory of Australia, a nonindigenous teacher named Geoffrey Bardon encouraged elders to use boards and acrylics to represent Dreaming designs. Using various abstracted techniques and a canon of symbols, artists rendered Dreaming stories in a permanent medium, although they obscured sacred designs from the uninitiated public. This new method of communicating Dreamings spread throughout central Australia, and for the first time artists had the opportunity to create art for public display. Today a network of art-producing communities crosses the country’s vast expanse. The flourishing of Aboriginal art over the past thirty-five years is one of the most exciting developments in international art.

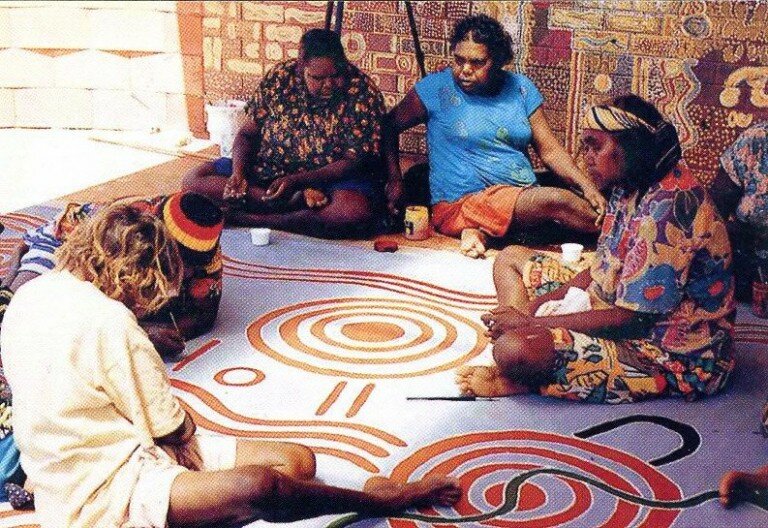

Painting with acrylics was initially a male occupation, with women sometimes allowed to fill in the backgrounds. In the 1980s women painters began to create their own work, and during the last decade they have received greater attention than their male counterparts. Often supporting their families and communities through art sales, women have become major figures in Australia’s contemporary art scene and in the global art market. At the 1997 Venice Biennale, the three artists chosen to represent Australia were Aboriginal women. In 2005, the winners in all five categories of the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards – the most prestigious indigenous art awards in Australia – were women.

Women artists have proven to be extremely resourceful and imaginative in creating new ways to represent the ancient Dreaming stories. In fact, the main reason to consider Australian Aboriginal art as a contemporary art form is that artists’ responses to the Dreamings are constantly evolving. The artists incorporate cultural identity, and spiritual character. As the artist Kathleen Petyarre explained, ‘You’re holding onto the country by doing that painting.’

Dreaming Their Way: Australian Aboriginal Women Painters is a groundbreaking exhibition of art by thirty-three indigenous Australian women. The first of its kind in the U.S., the exhibition presents over seventy works of art, from intensely colorful canvases to intricate bark paintings, all demonstrating women’s bold and often experimental representations of their heritage. Many of the paintings are simply exhilarating, with their bright colors, complex compositions, and a sheer joy that seems to emanate from the canvas. Their exuberance often stands in contrast to the circumstances under which they were made, including poverty in many communities. With few exceptions, the artists in the exhibition have not attended formal art schools in the Western sense but were trained through apprenticeship with senior painters and owners of Dreamings who ensure the correct depiction of their stories.

It is vital to understand that there is no single style of Australian Aboriginal art. Immense diversity exists within the cultures, languages, and traditions of Aboriginal people as well as in their environments. While it remains difficult to generalize Aboriginal art, some similarities in material, style, and subject are recognizable in certain geographic areas.

Utopia, situated in Central Australia, is a collection of communities recognized as one of the first areas where women artists flourished. In 1977 Utopia women learned the art of batik, a traditional Indonesian textile craft. This experience influenced the fluidity and spontaneity of the designs they would later apply to canvas, and flora and fauna remain the basis of their abstract paintings. Utopia is host to a dynasty of women artists, beginning with Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1916-1996). As a senior member of the Anmatyerre language group, and after decades of ritualistic artistic activity, Kngwarreye began painting on canvas in her late seventies. Her work received immediate attention from critics, collectors, and fellow artists alike.

Unlike most desert painters at the time, Kngwarreye did not use stylized representations of animal tracks or concentric circles in her designs. Instead she employed richly layered brushstrokes or dabs throughout her abstract compositions. The Dreamings of her country, Alhalkere, northeast of Alice Springs, inform her work through geographical contours, seasons, plant and animal life, and natural and spiritual forces. Anooralya (Wild Yam Dreaming) was completed in 1995, one year before the artist’s death, and shows her free handling of paint using sweeping brushstrokes and a keen sense of color. The dynamic composition shows the wild yam, also known as kame, which is the artist’s name and one of the Dreamings of which she was custodian.

Kngwarreye was prodigiously creative, and it is estimated that she executed approximately three thousand works in an eight-year period. The artist worked in series, using diverse styles almost always on a large scale. She earned international fame and was represented posthumously in the 1997 Venice Biennale as one of three Australian artists selected. Among Kngwarreye’s nieces are seven skin-group sisters who are all artists, two of whom are featured in this exhibition, as is Kngwarreye’s great-grandniece.

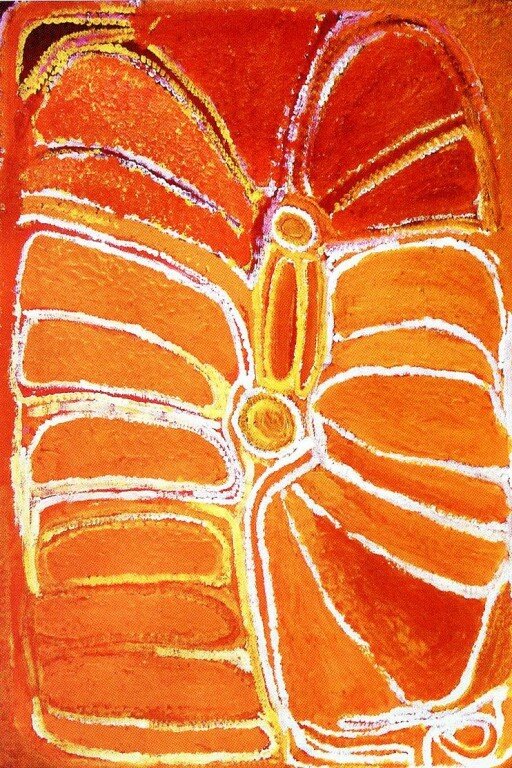

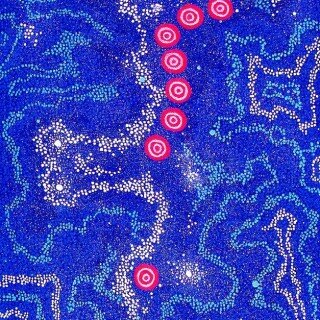

Kimberley, a region northeast of the Great Sandy Desert, is known for a diversity of artistic styles, from figural depictions of ancestral spirits to more formal landscapes in the Western sense. South of Kimberley Plateau lies Balgo Hills, home to the Warlayirti Art Centre. Here artists utilize extremely bright colors and a free handling of paint in their work. Currently the community’s best-known artist is Eubena Nampitjin (born c. 1925), an esteemed law woman who was taught traditional healing skills by her mother. She was raised in the lifestyle of a nomadic hunter, and still spends large amounts of time in the bush. Her bold, opulent paintings display intense hues of orange, red, or pink – a signature style she arrived at in 1989. Minma is an aerial landscape of the artist’s traditional country. It shows two circular rockholes that were formed when the malu, or kangaroo, escaped from the ground during the Dreaming. Typical of her recent works, the composition shows levels of thick layering executed in an assured, rhythmic process, often accompanied by singing.

Many Aboriginal communities in north Australia, the majority of which are located within Arnhem Land and on Bathurst and Melville Islands, are well known for their artistic expression. Due to the tropical climate and lush vegetation of Arnhem Land, the use of the eucalyptus bark as a painting ground is widespread. Designs are painted in natural ochres and pigments and are either very intricate, stylized representations, or abstract, complex compositions, all of which carry great spiritual significance.

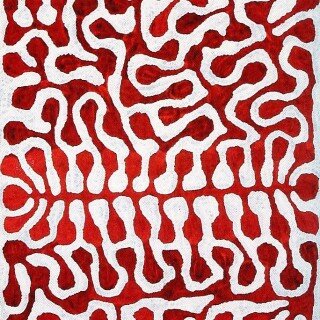

Kay Lindjuwanga (born 1957) lives near Maningrida in western Arnhem Land. She was taught to paint by her husband, acclaimed artist John Mawurndjul (born c. 1952), whom she began assisting in the 1980s. Employing a technique representative of Arnhem Land painters, Lindjuwanga uses a longhaired brush to apply layers of precise parallel strokes in a crosshatched pattern. Her images are abstracted representations of significant sites in her Dreaming. One such site is Bilwoyinj, where Nakorrkko, a father and son from the creation era, left behind a hunted goanna whose fat turned into the rock that still stands there today.

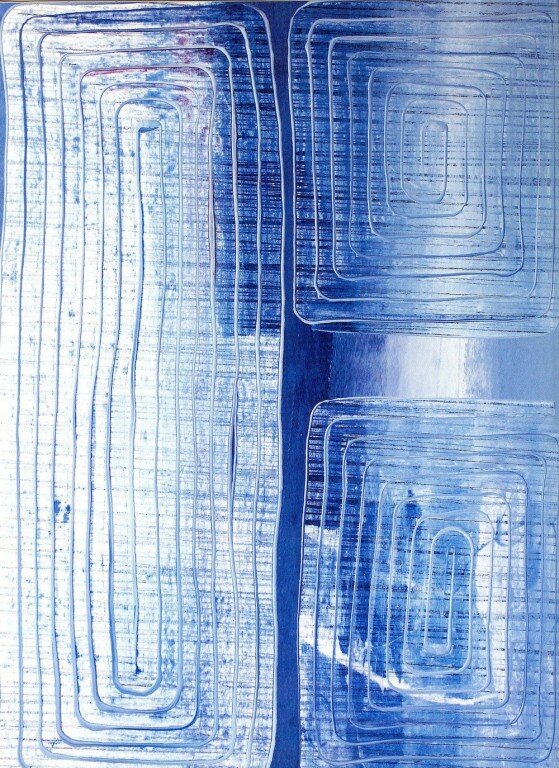

The Aboriginal communities on the tropical islands of Bathurst and Melville, located north of the continent, speak the Tiwi language and developed their art and traditions in relative isolation. Most Tiwi art is derived from ceremonial body painting and the abstract, geometric decoration applied to funeral poles and other ritual objects. While the artists display great individual differences in their work, all use only natural pigments and ochres. Their designs are often set against a black background and underscore the importance of ceremony in social life.

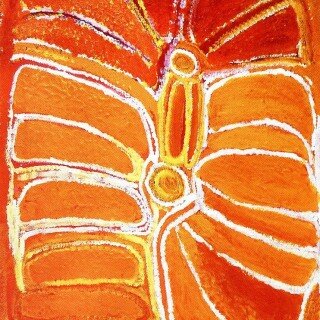

One of the most acclaimed artists of her generation, Kitty Kantilla (c. 1928-2003) possessed strong compositional skills and an assuredness of design. Deftly balancing shape against color and patterned against solid areas, her traditional images are incredibly refined and almost decorative. In 1997 Kantilla boldly reversed the Tiwi tradition of painting on black ground by painting on white instead. The resulting images are usually delicate and airy, as can be seen in an untitled work from 1997.

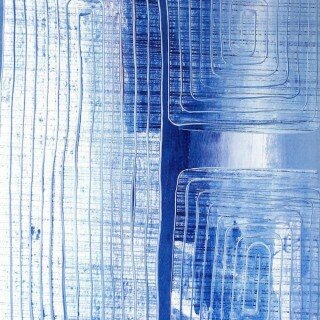

The northeast region of Australia is largely covered with tropical rain forest, which disrupts access to many communities during the wet season. Lockhart River, an extremely remote community on the east coast of Cape York, is home to the Lockhart River Art Gang, a ground of young artists, male and female, among whom Rosella Namok is the most acclaimed. Instead of using brushes or sticks, Namok paints with her fingers, usually on canvas, sometimes on paper – a practice that is inspired by traditional sand drawing. She has developed a range of symbolic shapes (including rectangles and ovals) that she uses not only to evoke traditional Aboriginal culture, but also to address contemporary life in her community. Although Namok has been influenced by the modern and contemporary art she has viewed in art galleries, she claims that ‘it’s listening to the old (Lockhart River) girls yarn that gives me the inspiration.’ In Para Way: the other way, Namok evokes racial difference – ‘para’ refers to white people.

Australian Aboriginal women’s innovations are bold and experimental, but the artists never give up their link to ancient tradition. Through their art, Aboriginal women express their relationships to their country, their understandings of the world and how it came to into being, and their responsibilities for maintaining and reproducing their culture. Their painting is also a political act, stating their rights to their land and asserting the strength of their culture.

Britta Konau is associate curator of modern and contemporary art and Rebecca Price is curatorial assistant at the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Konau, Britta and Rebecca Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way: Australian Aboriginal Women Painters,’ Women in the Arts (Summer 2006), 11-15.

Images:

1. Women painting Karrku Jukurrpa canvas. Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Association. Konau and Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way,’ 13.

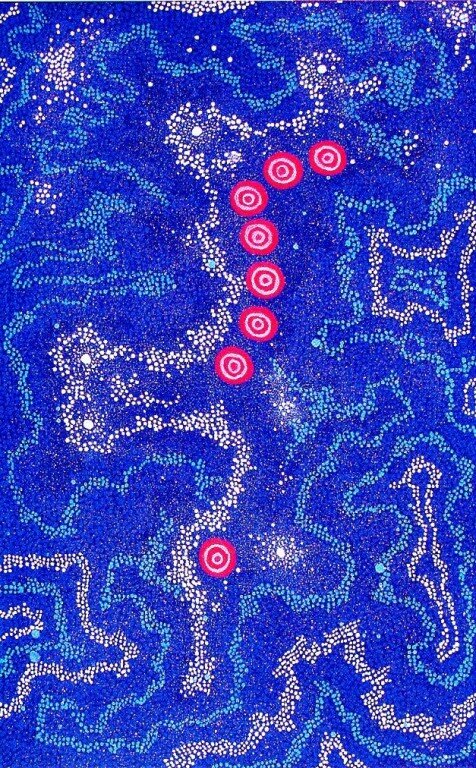

2. Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi’s Milky Way Seven Sisters Dreaming. Konau and Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way,’ 13.

3. Eubena Nampitjin’s Minma. Konau and Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way,’ 15.

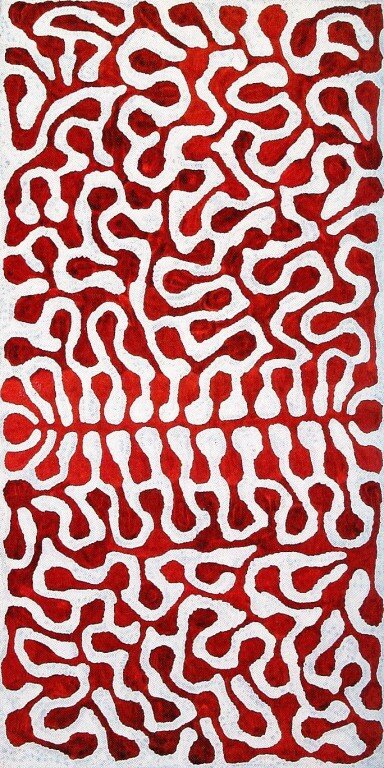

4. Mitjili Napurrula’s Uwalki: Watiya Tjuta (Trees). Konau and Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way,’ 14.

5. Rosella Namok’s Para Way: other way. Konau and Price, ‘Dreaming Their Way,’ 10.

MooreWomenArtists welcomes comments and a lively discussion, but comments are moderated after being posted. For more details please read our comment policy